There are perhaps no cells as significant to science as the ones known as “HeLa.” Eternally growing, they were used to develop the polio vaccine, provide information on HIV/AIDs, and more for half a century. The owner of these cells, however, had no idea, and until relatively recently, HeLa’s identity was a mystery.

Henrietta and her husband, Day Lacks

A life cut short

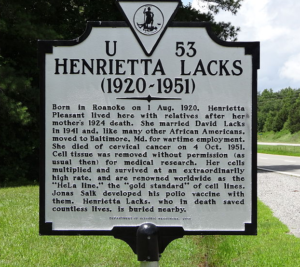

Henrietta Lacks was in 1920 with the name Loretta Pleasant. She went by “Henrietta” however. At the young age of 14, she gave birth to her first son, and a few years later, a daughter. She married the father, Day Lacks, in 1941. The couple and their children moved to Virginia and worked a tobacco farm, until a cousin persuaded them to move to Maryland. Henrietta gave birth to three more children.

Henrietta went to John Hopkins hospital, which was the only hospital in her area that treated African-Americans. She felt what she described as a “knot” in her womb, and after giving birth to her last child, she suffered a severe hemorrhage. She was eventually diagnosed with cervical cancer. In early August, John Hopkins admitted her for persistent, terrible stomach pain. She received treatment and blood transfusions, but remained at the hospital until she died on October 4th, 1951. Tests revealed that cancer had spread through her entire body. Henrietta was only 31 years old.

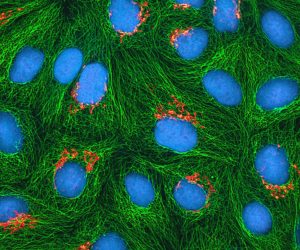

Henrietta Lacks’ “immortal” cells

While Henrietta received treatment for cancer, doctors took cell samples without her knowledge or permission. This was standard practice for the time. George Otto Gey, a cancer researcher and doctor, received the samples. For decades, researchers had been trying to grow cells in a lab, but they kept dying. When Gey examined Henrietta’s cells, however, he found they reproducing extremely quickly. They also didn’t die; they were essentially “immortal.” Gey cultured the cells and named them “HeLa,” after the first few letters of Henrietta’s name.

A stained HeLa strain sample

In 1954, just three years after Henrietta’s death, Jonas Salk used the cells to develop the polio vaccine. Everyone wanted these special cells and they were reproduced over and over again. They traveled around the world as scientists used them for research into every type of disease. In 1955, scientists cloned HeLa cells, marking a major milestone. Since the 1950’s, 20 tons of HeLa cells have been reproduced.

Scientific ethics questioned

With just the HeLa designation as a clue, the identity of the cells was not widely-known. The cells were treated like public property. In 1988, a student in a biology class learned that the HeLa cells belonged to a black woman named Henrietta, but that was all the teacher could tell her. The student, Rebecca Skloot, became obsessed: she needed to know more. In graduate school, she began tracking down the family. Her project became the 2010 best-seller The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks. In 2013, researchers published a DNA sequence of a strain from HeLa. This revealed medical information about Henrietta and all her descendants. Researchers hadn’t even bothered to inform the family the information would be released: they only found out because Rebecca Skloot told them.

That same year, the National Institute of Health finally allowed the Lacks family a level of control over access to the DNA sequences, as well as a future acknowledgment in papers. Henrietta’s story has since been made into a TV movie starring Oprah Winfrey and Rose Byrne, with Renee Elise Goldsberry as Henrietta Lacks.

———-

DNA is a lot more flexible than you might have imagined. Read here to find out about “grinders” and how they are experimenting with their genes.

Photo by Emw