Nature versus nurture, or, better said, genes versus the environment – that is an age-old battle that has puzzled us since we began meticulously studying the roots of human intelligence. Are we born into already determined cognitive limits, or can we acquire additional potential by making the right decisions and having exposure to favorable conditions? What is the prevalent factor that shapes mental performance?

Not long ago, in an attempt to avoid any kind of social and racial prejudice, equality at birth reigned supreme, giving individuals the same clean sheet to work with. However, recent studies are finally threatening the status quo with substantial evidence. Genetic determinism is gradually outweighing the sculpting abilities of the environment.

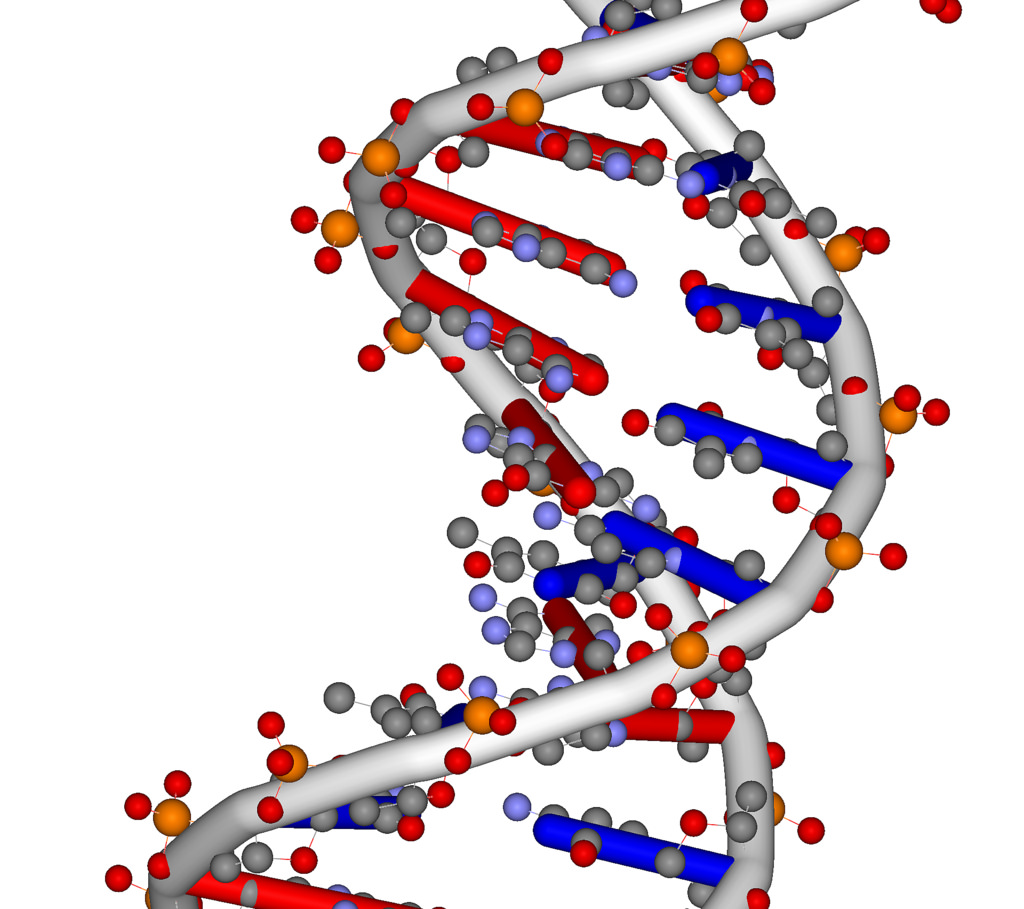

Mapping the human genome was a massive initiative, one that was formally declared completed in 2003. A team of European and American scientists led by geneticist Danielle Posthuma picked up the trail and managed to identify 52 genes linked to superior mental abilities. The breakthrough was announced in May 2017 and came after compiling data from 13 earlier studies that linked genetic markers with scores for intelligence tests.

Analyzing human intelligence often struggles with offering an unambiguous definition to the term. Most studies rely on standardized tests covering a vast array of abilities that society collectively perceives as belonging to general intelligence. Nevertheless, applying the same tests to a big number of subjects requires an impeccable methodology and is currently the biggest obstacle. Finally, scientists zooming in on the intricacy of human intelligence have the daunting task of accounting the environment’s role in it.

Another problem lies in highlighting the anatomy and physiology of intelligence. Which part of the brain has a part to it? There is evidence that brain size accounts for variance in intelligence across individuals, but the argument is not yet definite. The network of neural connections has long been regarded as defining for intelligence, but charting that seems to be an impossible challenge. That is where scientists contemplate a different approach. Their dream is to take brain cells, grow neural connections between them, and have a closer look at the “mini-brains.”

The idea that genes and intelligence are somehow connected is derived from the study of identical twins. A research extended throughout the 1990s pointed out that identical twins are more similar than fraternal twins regarding IQ. The Minnesota Twin Study also made it clear that identical twins, despite originating from the same fertilized egg, do not have identical DNA.

Taken as a whole, the last decades of genetic analysis and this year’s breakthrough significantly altered our earlier belief that intelligence is mostly relatable to upbringing, education, social interactions, and the environment in general. It remains to find out just how much we owe to our genes.