Famed for her self portraits and feminist identity, Frida Kahlo at her core defined herself in her own terms and took control of her image. The Brooklyn Museum curated the exhibit Appearances can be Deceiving to present a treasure trove of personal items of Kahlo’s that were locked away in private until 2004. The current exhibition presents clothing and jewelry from Kahlo’s vibrant wardrobe, photographs, and film alongside pieces of her art. Through these items, we can examine the various factors that contributed to Kahlo’s complex identity and modes of creativity.

Kahlo embodied several identities. First and foremost, she was Mexican. Getting involved politically in her community and joining the Mexican Communist party is where she meets Diego Rivera, her husband for many years. As the daughter of a German immigrant and Oaxacan woman, Kahlo embraced the country she was born in. Though she adamantly did not believe in religion, Kahlo adopted the traditional apparel of Tehuantepec, a religion in Southern Mexico, which is where her mother grew up. Much of her wardrobe reflected this, the bright colored huipil top, skirt, and holán (ruffle) would become her signature look. Many of the photographs that were on display highlighted Kahlo’s clothing choices and relationships. From pictures of Kahlo with her family growing up to her wedding day with Rivera, all the photos displayed echoed the various identities Kahlo embraced during her life. With many photos having taken place in Gringolandia, (what Kahlo called the United States), the exhibition was able to highlight her love-hate feelings with the several she lived in. Kahlo herself said, “The gringas really like me, a lot take notice of all of dresses and rebozos that I brought with me. Their jaws drop at the sight of my jade necklace…” While primarily for the cultural and political statement, there was a second reason that Kahlo adopted clothing.

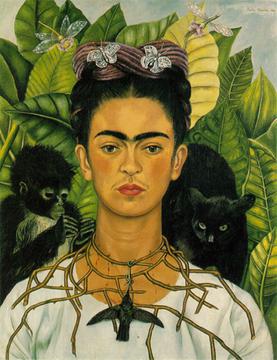

Self-Portrait with Thorn Necklace and Hummingbird (1940)

Kahlo called herself “broken” because of all of the illnesses and injuries she sustained over her life. Adopting the Tehuantepec style of clothing helped to hide her disabilities from the world. With skirts reaching to the floor, her legs were hidden, and the hiupil did not ride up her back and was spacious enough to cover medical corsets. Her suffering is what she channeled into her paintings. The first self-portrait she ever painted was during the recovery period of the traumatic vehicular collision she was in where a handrail pierced her pelvis. Though she was limited to laying flat on her back, she was able to draw and paint with a canvas rigged to hang above her. She also had a mirror hung above her in order to see herself to create such self-portrait. Even as she grew older, Kahlo continued surrounding herself with miros to compose her self-portraits, as well as to compose her appearance.

As early mentioned, Kahlo took control over her own image. From paintings to photos, she only allowed the viewer to see what she wanted them to see. The exhibition had only one of Kahlo showing her medical, plaster corset. Such corsets she truly made her own by painting on them in fresco style. She considered her multiple medical devices as her “second skin,” which she revealed selectively. In the photo in the exhibit, she kneels on a bed, huipil lifted, as she stares at the camera. Kahlo also lets her viewers see this emotional, pained part of herself in several paintings and sketches, but The Broken Column (1944) as one of the more famous ones. In it, Kahlo is sitting erect wearing an orthopedic corset with her torso open, revealing a crumbling column replacing her spine.

Lastly, Kahlo embraced gender fluidity, though at the time there was no such language. Having embraced characteristics of herself that she felt were man-like, Kahlo would at times dress androgynous. In a family photograph from 1926, Kahlo dressed herself in a three-piece suit, typical apparel for men of those days. Similarly, the painting Self-Portrait with Cropped Hair (1940) illustrates Kahlo in an ill-fitting suit, heeled shoes, and earrings, with her cut hair littering the ground. The portrait and altered ballad lyrics enforce her act of self-transformation to an alternate androgynous being.

Kahlo endured many sufferings during her lifetime. Though the streetcar accident is a big one, she quotes Diego as her second one. Kahlo used her art as a way to communicate her feelings and channel them into something that she could share with the world. As a female with a strong voice during a time that it was hard to be heard, she was loud enough to be noticed and still be a major figure today. The exhibition will be open in the Brooklyn Museum until May 12th, 2019.