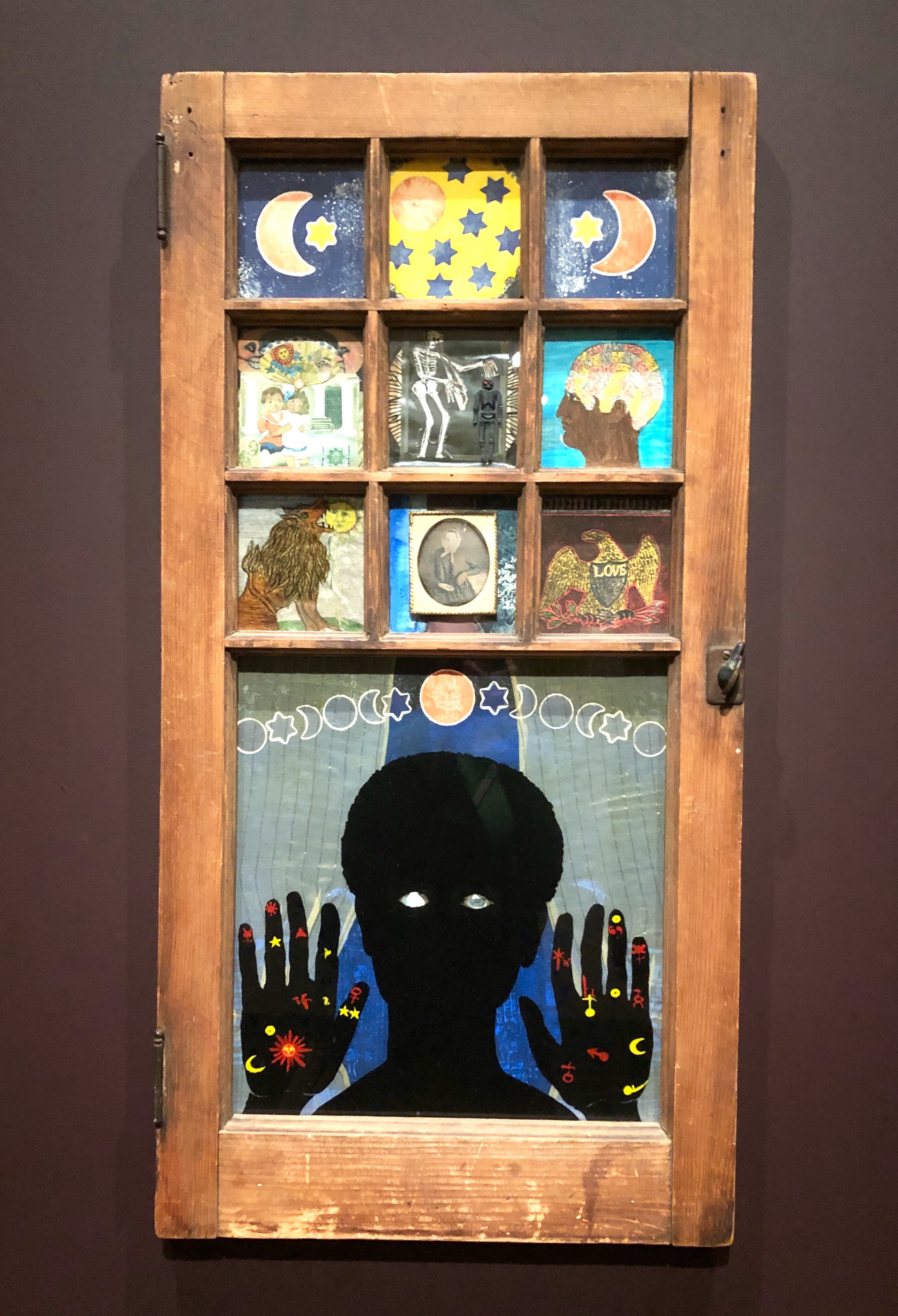

As a young girl who frequently collected, assembled, and repaired objects, Betye Saar has become an icon of assemblage art. Initially a printmaker, Saar has evolved into more than that. The Museum of Modern Art’s (MOMA) exhibition, The Legends of Black Girl’s Window looks at the relation between her printmaking practice and incorporating 3D objects, which is first illustrated in her piece Black Girl’s Window (1969). This exhibition further explores themes of family, history, and mysticism, which Saar’s work has been rooted in from her earliest days.

Black Girl’s Window 1969

Saar grew up, went to school, and still currently lives and works in California. Though she began her graduate career with the intentions of teaching design, she took a printmaking class that changed everything. Saar calls printmaking “a great seducer” and her “segue from design into fine arts.” While she was in graduate school, she got married and had three children. Anticipation (1961) is an autobiographical depiction of Saar pregnant with her third child that captures the joy of the approaching birth and the exhaustion of pregnancy. The viewer also sees Saar’s interest in different textures and patterns within this painting from the figure’s dress to the wall she leans on.

In the late 1960’s, Saar gained inspiration to create assemblages. From found object sculptors Joseph Cornell and Simon Rodia, Saar felt that seeing these objects put to artistic use was magical. Specifically Rodia’s creation of his Watts Towers was greatly inspirational for her as she witnessed his building them in childhood. As Saar began exploring assemblage work for herself, she used everyday objects like many others of that time, but used them to examine the realities of African American oppression and the mysticism of symbols.

Saar has talked about her use of materials as being not only literally recycled, but also recycled emotions and feelings. Through her anger regarding segregation and racism in the States, she made art that expressed it. As a part of the Black Arts Movement in the 1970s, Saar tackled racism in her usage of African American folklore and icons in an effort to contextualize them. In looking at her piece, Black Girl’s Window, which is the theoretical epicenter of the MOMA’s exhibition, it demonstrates the convergence of black power, mysticism, spirituality, and feminism. As another autobiographical piece, Black Girl’s Window points at Saar’s interests and reflections of her family history, astrology, and the unknown. Made from an old window with hinges, a painted silhouette of a girl is pressing herself to her window, eyes staring out, with bubbles of thought in each small square space above her head. The center of those being death, which Saar has talked about as being the center of everything and being a time of transition where the past is linked with the future in a similar way to a window being the link between outside and inside.

Lo, The Mystique City 1965

Saar has mentioned herself that she sees a thread of curiosity regarding mysticism throughout her pieces from her beginnings in printmaking in the 1960s, through her assemblages, now tying into her current installations. She uses fragments of everyday objects as remnants of memories and emotions and combines them with components of technology as a way to investigate the past and future simultaneously. In this way, she considers are to become a bridge. On her website, betyesaar.net, she has the following poem on her homepage:

Curiosity

about the unknown

has no boundaries.

Symbols, images, place and cultures merge.

time slips away.

The stars, the cards, the mystic vigil

may hold the answers.

By shifting the point of view

an inner spirit is released.

Free to create.

Betye Saar

1998

Saar has utilized her own innate curiosity and history to form her artistic identity. The Legends of Black Girl’s Window illustrates the depth of Saar’s work, which is embedded in printmaking at its core. This exhibition also celebrates the MOMA’s recent acquisition of 42 rare, early works of Saar’s and is the first examination dedicated to her work as a printmaker. This exhibition will be open until January 4th, 2020.