The Colorado potato bug seemed harmless enough. In 1824, entomologist Thomas Say recorded its existence and collected samples from the Rocky Mountains. At the time, the insect was eating the buffalo bur. However, in 1859, the yellow-and-black bug revealed its true viciousness. It discovered the potato plant, and began destroying them, beginning in Nebraska and moving to the east. The larvae were especially effective, and could cause a 100% loss in a potato crop. By 1874, the bug hit the Atlantic Coast.

Americans warned Europe about the bug. Potato imports from America were immediately banned in several countries, like Germany, France, and Belgium. However, their efforts were futile. By 1877, the bug began establishing itself, and grew in population during WWII. The species was so good at destroying crops, the French had once drafted a plan on how to use the potato bug against Germany in WWI. During WWII, the Germans tried their hand at creating a new, similar bug. Neither countries succeeded.

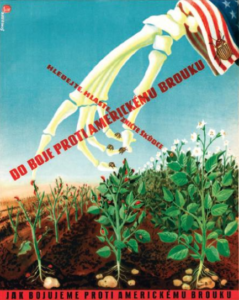

By the end of WWII and beginning of the Cold War, the Soviet zone of Germany – East Germany – was infested. Half of their potato fields were attacked in 1950. Most relied on the potato as their main source of food, so the bugs were truly devastating. The insect was called “Amikfaer,” which translates to “Yankee beetles.” The government began an intense propaganda campaign, saying that American planes were dropping potato bugs on crops. The People’s Republic of Poland and Czechoslovakia joined in, and communist flyers and leaflets were circulated widely. Officials compared the bug to the atomic bomb, saying that though the potato bug was smaller in size, it was still “a weapon of the US imperialists” against East German farmers.

Without effective pesticides, farmers had to deal with the infestation themselves. Children were usually the ones who had to go out in the crops and collect eggs, larvae, and beetles by hand. Children’s books were released, complete with instructions on how to find the bug and kill it by drowning it in benzene or alcohol. The government organized regular bug-collecting days, known as “Sonderuchtage,” or “Special Search Days,” where everyone in town would go out to the fields.

Propaganda poster in Russian shows a skeleton robed in American color dropping potato bugs

The government knew Americans weren’t dropping bugs. An internal report later revealed that scientists agreed that the skyrocketing potato-bug population was due to the good climate and lack of pesticides. However, the infestation provided an opportunity to sow mistrust and hatred of the Americans, so the communists took it. Many of the civilians believed the government, but just as many – especially younger people – knew how absurd the idea was.

The Colorado potato bug is a bit of celebrity in Europe, though a much-feared one. Seen on stamps in countries like Romania and Austria, governments hoped it would draw attention to the issue of infestation. In 2014, during the political upheaval in Ukraine, pro-Russians were called “kolorady,” which is the Russian/Ukrainian term for the insect. The reason? Pro-Russian separatists often wore St. George’s ribbons, which had black and orange stripes.

Today, you can find the Colorado potato bug all over North America and Mexico, except in Alaska, California, Nevada, and Hawaii. In Europe, it spreads across 16 million kilometers, or over 6 million miles. If you find potato bugs in your garden (they like eggplants and tomatoes, too), insecticides don’t really work because the insect has become resistant to most treatments. The old-fashioned way of removing the eggs and larvae by hand has proven to be the best method, though it’s a pain if you have a big garden.

—————

The Colorado potato bug devastates crops, but is otherwise harmless to humans. A not-so harmless insect? The kissing bug.